On July 1st, Elon Musk declared Tesla to be a “real car company”, after overcoming “production hell”* and hitting ambitious targets for its new Model 3. But what makes a “real” car-company? And is it still aspirational?

Indeed, it’s a difficult time to be a “real car company”. Traditional automobile manufacturers are caught in a twilight zone between the old-world and the new. They must understand multiple, new battlegrounds (electrification, autonomous, sharing), interpret the activities of their various new frenemies, and fight on various fronts. All while still sustaining a lot of dead weight.

“To know your enemy, you must become your enemy.”

– Sun Tzu

Read the annual reports of virtually every automobile manufacturer, and you’d be forgiven in believing that “car company” has become a dirty word. Most have committed to becoming “mobility companies” or “mobility service providers”. Many have committed to some combination of Zero Emissions, Zero Accidents, Zero Fatalities, Zero Congestion or Zero Distractions (all of which seems flatteringly familiar) – or, a world of on-demand, autonomous, shared, urban mobility.

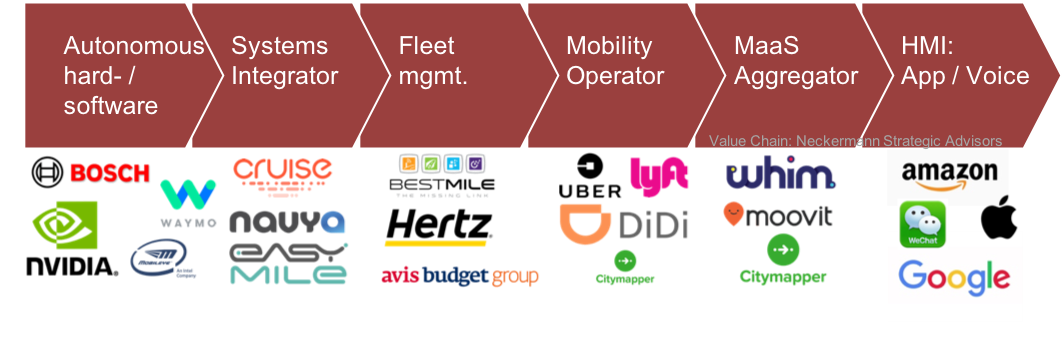

But the new value-chain for on-demand, autonomous, shared mobility looks very different from what the OEMs are accustomed to (see below, with selected players). There is no marketing and sales area, there are no dealerships, and manufacturing is a question of integrating hard- and software made by some unfamiliar suppliers. The end-customer is far removed from the manufacturer, intersections are new, and competitors are also different.

To assemble the various parts of this new value-chain, GM has invested in Lyft and Cruise. Ford bought Chariot, TransLoc and others. Daimler’s long list of investments includes MyTaxi, Via, and Ridescout. BMW’s net spans from electric buses (via iVentures) to maps, sensors and charging. Toyota has invested $1 billion in Grab, adding to its mobility portfolio (that also includes an investment in Maas Global). The deals made by OEMs are numerous, but none yet covers the entire value chain. Above all, they also pale in comparison to the over $20 billion in investment made by Softbank – the undisputed leader in assembling elements of the entire autonomous, on-demand mobility value-chain.

Being committed to both the old-world and the new is like maintaining two households: expensive.

The issue is, of course: even while automakers invest into on-demand, autonomous mobility services, they still need to serve traditional buyers of internal-combustion-engine, privately-owned trucks and cars. Unlike the disruptors, OEMs are spread thin, having to make investments both into their “cash cows” and into the future most agree is coming.

For all of the investments that these “traditional” car companies are making in electrification, in shared mobility, and autonomous technology, some of their old-world investments are mindboggling. Perhaps car companies will someday be well positioned to leverage their own strengths, but first, they would need to shed the dead weight. Some aren’t.

Mazda proudly claims to be committed to diesel (their share price is also at a 5 year low). JLR is building a local assembly line for diesel engines in India. Daimler just completed a “green” diesel and petrol engine plant in Poland for €500 million. All these investments, while the diesel engine – which was really only relevant in Europe anyway – is now sinking into oblivion. It’s hard to see how these investments will ever be recouped.

The dead-weight extends to branding and infrastructure. Perry’s recently celebrated the “newest and largest” Ford dealership in Europe. DS – formerly a Citroën subbrand – is insisting that dealers now build separate showrooms for the brand, just as Renault is doing for Alpine. While VW, Vauxhall and others have terminated dealership contracts, perhaps Ford, Renault, and Citröen know something we don’t about a resurgence of the dealership model? These really are odd decisions, especially as there is little notable activity from the Renault-Nissan Alliance in shared and autonomous mobility, and Ford may be “falling behind” in mobility.

What’s patently absurd, however, is when carmakers still release new vehicles without a view toward electrification. Brands such as Volvo, Peugeot, Jaguar Land Rover and others have committed to releasing every single new vehicle with electrified options (some sooner, some later). Meanwhile, BMW’s brand-new flagship 8-Series will be available with a biturbo V8 and a 320 horsepower diesel, but without a PHEV or BEV option. Did someone miss the memo?

The new BMW “flagship” Diesel Coupé will get its gearbox handed to it 0-100 km/h by most every electric SUV and saloon on the market.

OEMs and industry ministers claim they need diesel engines to comply with CO2 regulations (even subsidizing the purchase of new diesel engines with an absurdly named “environmental bonus”). Of course this argument is a farce; building more electrified vehicles accomplishes the same goal (and they are always cleaner). In truth, the traditional OEMs temporarily need diesel sales to keep their production plants running, while their EV strategies catch up (to Tesla) and their model portfolio gets updated.

On not becoming a “real car company”

So what attracts investors to Tesla? To Byton, Faraday Future, or to any of the many privately-held mobility companies (like Lyft)? They are purebreds. For better or for worse, they are holistically dedicated to the future of the industry. They are unencumbered by sustaining a legacy of development, production and staffing for diesel-engined vehicles. They are also not tied into long-term dealership contracts. Because while these are clear strengths of today’s “real car companies”, what made them strong over the last century, is not what will allow them to survive the next decade.

* In spite of their claimed experience, “real car companies” also have their own “production hell”; VW has had to close its main production plant for several days per week as it can’t get its engines to comply with WLTP. Audi has suspended deliveries of many of its most popular models. Ford (who arrogantly got into a Twitter feud with Elon Musk), halted production of its pickup-truck plant on May 2nd. It seems, all “real car companies” go through a “production hell” at some point.

This article is part of a series of opinion-pieces written by Lukas Neckermann for Hyperion Executive Search.