As urbanisation and online-shopping each intensify, cities and communities are being challenged to find space for a flood of new transport options for both people and freight. It’s a challenge that will determine their fate over the next decades. It’s lead, follow, or get out of the way in the race for liveability and economic success.

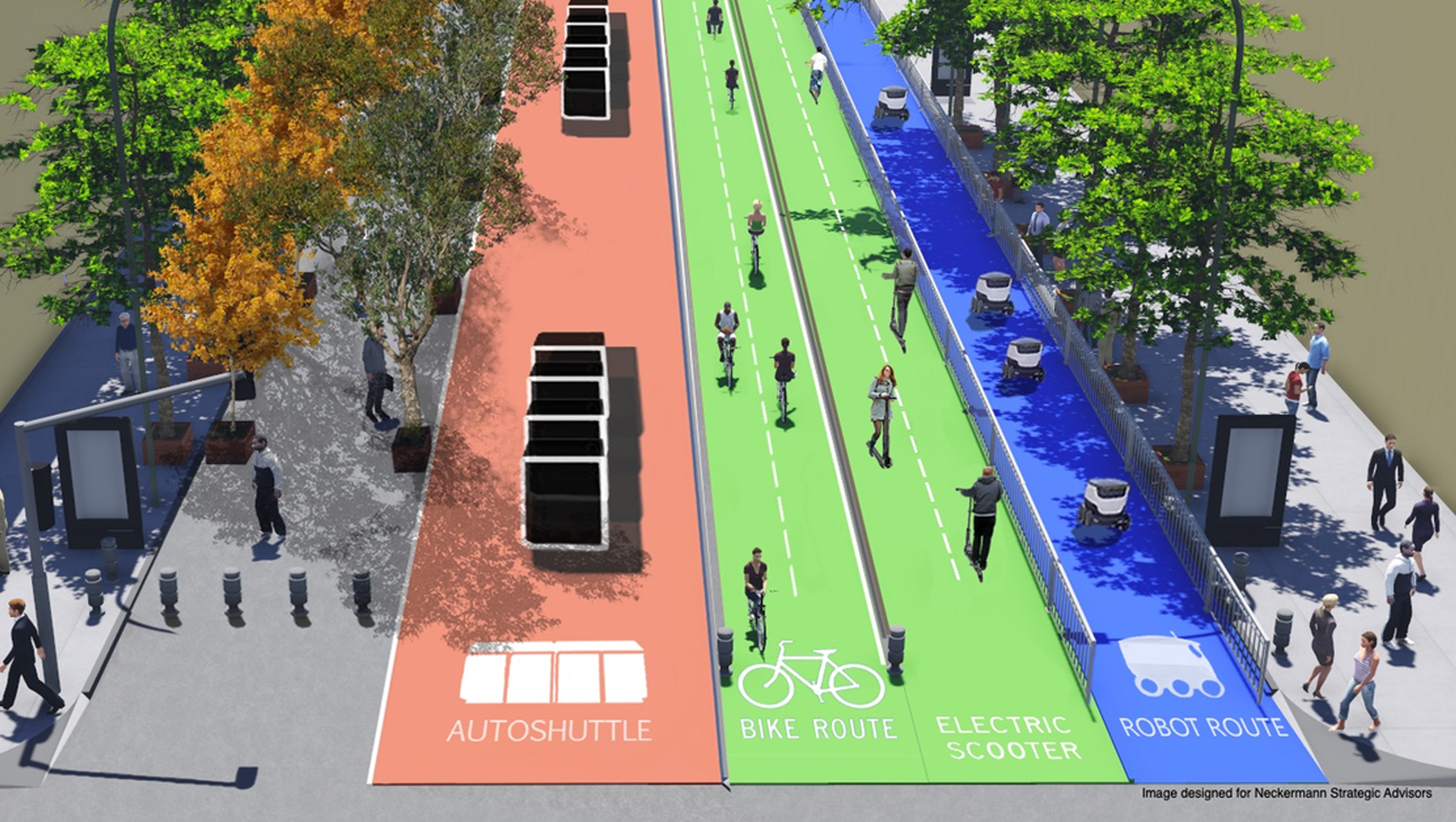

One key, is recognising that the car and van are becoming the least-efficient modes of urban transport. Sure, road-diets are a good start. Longer-term, however, implementing more infrastructure for pedestrians, bicycles, e-bicycles, scooters, e-scooters, robotic delivery, and autonomous public transport solutions is the logical consequence. The image above (banner) is just one suggestion.

In reality, many cities are today still struggling to cope with the rapid rise of carsharing and ridehailing vehicles. I shake my head when I hear from planners who assert, “there’s simply no room for carsharing, bike-lanes, and ridehailing drop-off zones” – they don’t see the woods for the trees. Mobility-as-a-service (which includes ridehailing) is part of the solution, but some city-planners and urbanists are still (somewhat lazily) blaming Lyft, Uber and others for causing (economically disastrous) congestion, rather than inefficient urban space allocation. The fact is, consumers actually enjoy these new transport options, are (mostly) prepared to share, and even prepared to reduce car-ownership, as long as transport options are sustainably and reliably provided. If this is given, then cities can finally reclaim real-estate currently allocated to car parking.

Of course, public transport remains a most efficient option for moving lots of people; however, its lack of short-term scalability and variability also means that there are thousands of empty and misallocated buses driving around cities. Scalable concepts, such as NEXT Future Transportation, and variable, on-demand systems such as Citymapper, Via, MOIA and other pooled ridehailing services can provide genuine solutions – for users, for cities, and even for employers within those cities.

Ten times as much transport in the same space as a car

Bicycles have been a last-mile transport solution for two centuries; the more recent availability of electric bicycles, bike-sharing, and dedicated laneshave thankfully turbocharged their adoption and use. Even more spectacularly, electric scooters have created a “micromobility revolution” – to the surprise of most cities.

Some are calling to ban e-scooters, many have no regulations for their use; most have no space to park them. So to their credit, Bird and Lime have each delivered creative solutions for parking and charging spots, as well as enabled users to find and report good and bad parking. The more clever cities are coming to embrace the trend.

Moving goods

But beyond passenger transport, the next wave to hit city transport-planners, will be delivery robots. Britain’s largest online grocer, Ocado, last year trialled autonomous delivery vans, in the US both Kroger and Wal-Mart are preparing for driverless deliveries, and Toyota is imagining that stores and restaurants will come to you, not just deliveries. A bit smaller, both Starship and Eliport envision thousands, perhaps millions of autonomous delivery vehicles making package-deliveries across communities. To provide the comfort, the reliability and the timeliness that consumers expect, they will require space.

Already today, logistics companies are increasingly using cargo bicycles in cities – in various sizes. UPS, for example, is piloting a concept whereby containers of cargo are transferred from trucks to cargo-bikes for last-mile deliveries. It’s a welcome, zero-emissions idea, but even these bikes need a certain amount of space. With three wheels, should they use bicycle lanes or streets? Decisions, decisions…

Smart cities by design

Barcelona is among the progressive cities that has taken a first step toward regulating traffic more rigorously – declaring “Pedestrians First” in Superblocks that effectively remove 2/3 of transport infrastructure for cars in those areas. In the right image (below), non-resident vehicles, as well as commercial vehicles and public transport, are restricted from two of three streets. Residents are permitted to drive into their zone at minimal speed, and traffic is concentrated into the remaining thoroughfares. Barcelona is not alone in reducing their car-centricity; Copenhagen has had car-free zones for decades; Paris, Madrid and others are unveiling their car-free concepts, although each may still struggle with individual modes of new mobility.

Every city and community is different; there are no cookie-cutter solutions. But there is an urgency. The time is now to implement concepts that embrace new modes of mobility, and thereby enable (and ensure) decades of growth.

Lukas is Chief Strategist at Splyt and Managing Director of Neckermann Strategic Advisors – a consultancy with a focus on the mobility revolution. He is author of the book “Smart Cities, Smart Mobility“, and advisor to NEXT Future Transportation and Eliport (both mentioned in this article).

This article first appeared on LinkedIn.